Intracellular bacteria use various tricks to control eukaryotic cell biology to their advantage, allowing them to get into and out of cells, move around, and pilfer resources. Some of the best studied examples of bacterial manipulation are shown below.

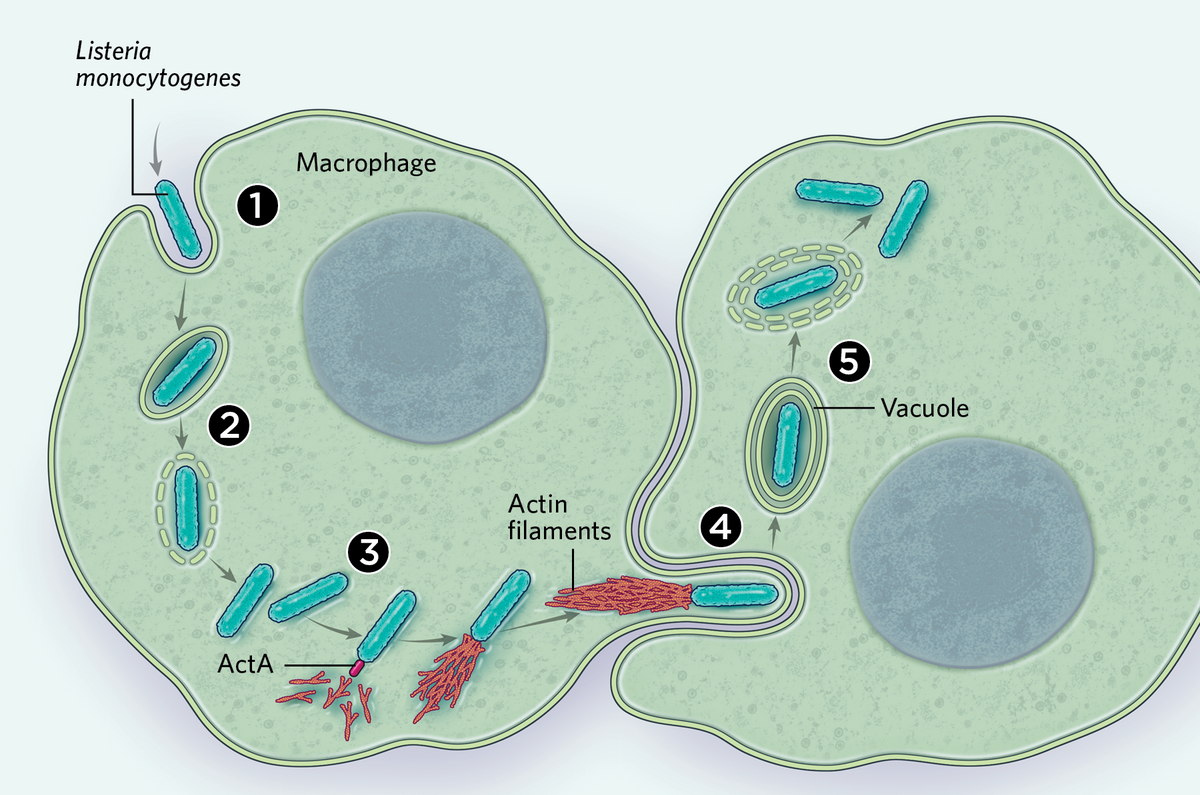

Listeria gets its host to build it an actin tail

Some intracellular bacteria use the host cell’s actin supplies to build their own transport system. The foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes infects immune cells called macrophages by being taken up into a vacuole (1) before entering the cytoplasm where it lives and replicates (2). There, it uses a protein called ActA to recruit the host cell’s actin polymerization machinery to construct a tail of actin filaments behind it (3). This process gives the bacterium a means to propel itself around and lets it push on the host cell membrane, forming protrusions into neighboring cells (4). Those neighbors take up these protrusions as vacuoles, from which Listeria escapes to access the cytoplasm and begin the cycle again (5).

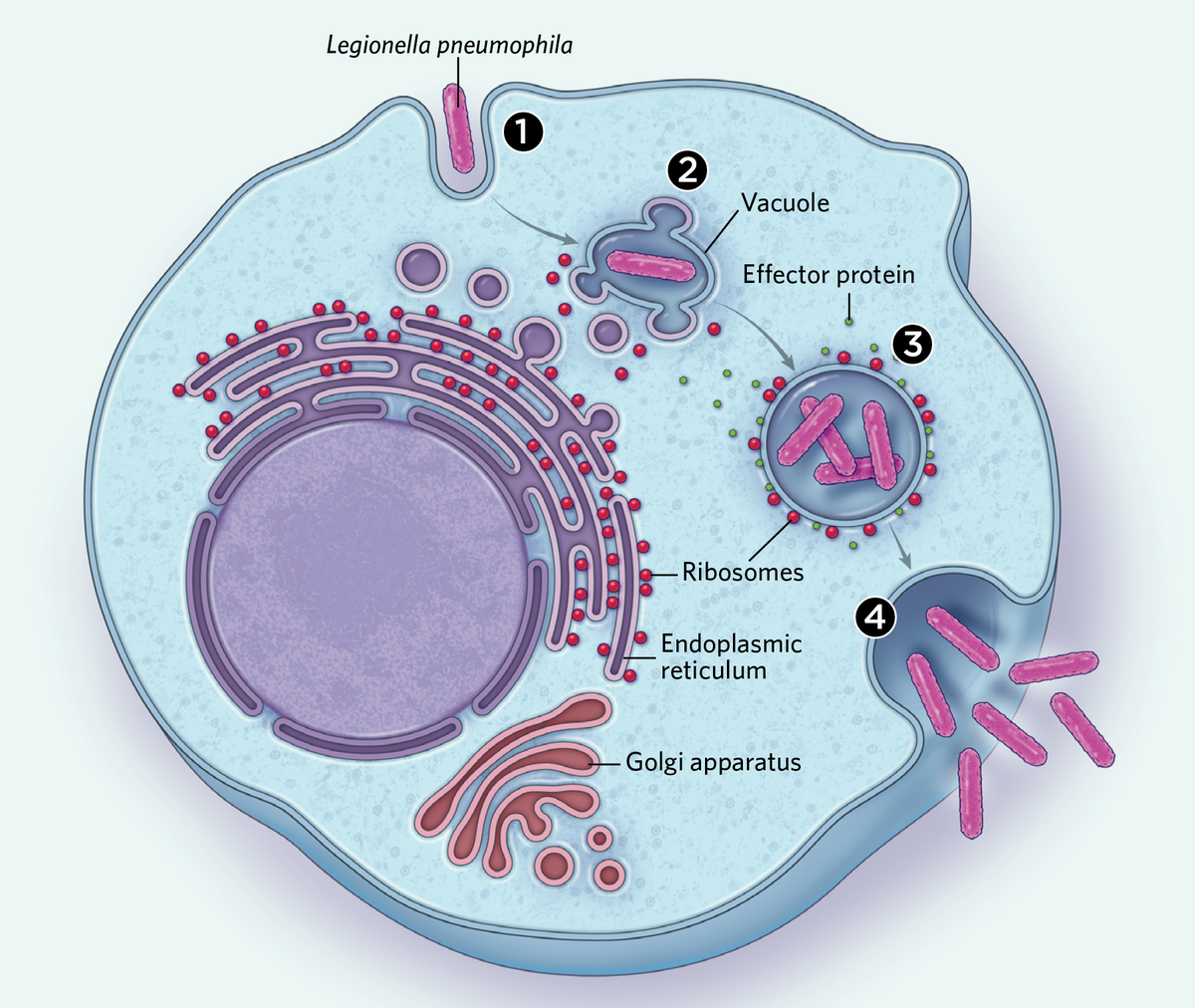

Legionella takes control of host membranes

Some intracellular bacteria, such as Legionella pneumophila, inhabit membrane-bound compartments inside host cells (1). Once there, the microbes typically interact with host membranes and secrete so-called effector proteins that help the microbes wield control over them (2). Legionella in particular interacts with the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum, pilfering some of the organelles’ proteins and rerouting their vesicular traffic. Later, the newly formed membranes become studded with ribosomes (3) that may help the bacterium make certain host proteins—or could simply be a byproduct of the membrane’s ER-like identity. Legionella replicates inside this compartment before bursting out of the cell (4).

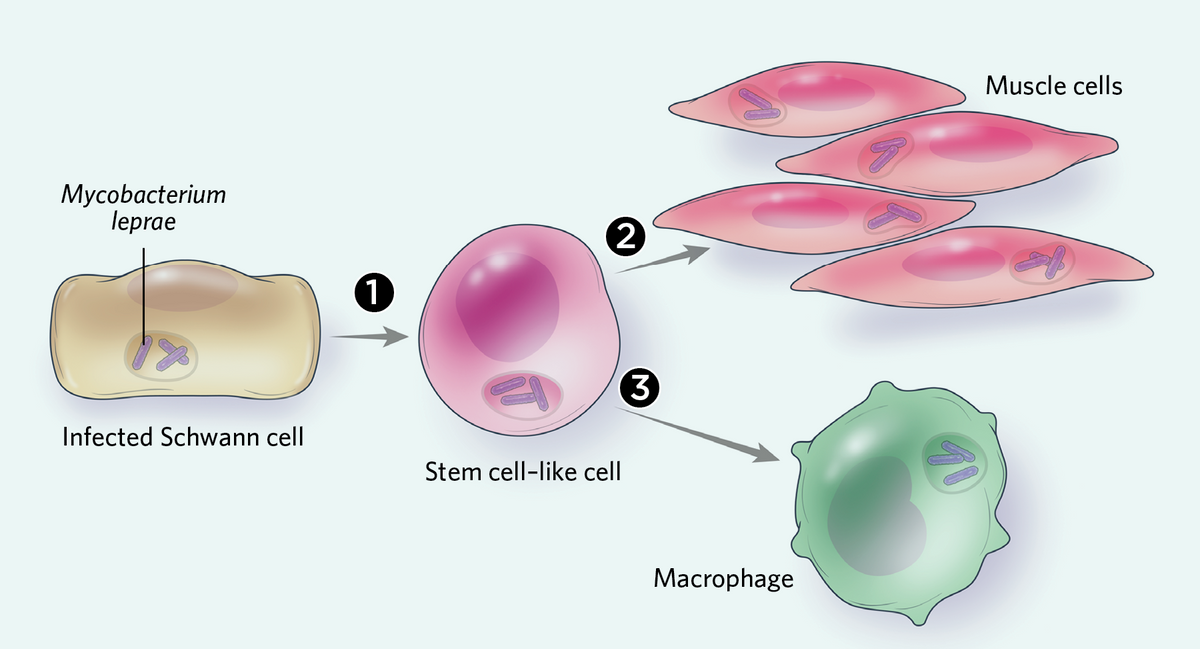

Mycobacterium leprae reverts its host to a stem cell–like state

Mycobacterium leprae, which causes leprosy, takes cell reprogramming to an extreme by reverting its Schwann cell host into a stem cell–like state (1). These cells can then redifferentiate into muscle cells, for example, perhaps spreading the bacterium to other tissues (2). The reprogrammed cells can also pass the infection on to macrophages, which then form structures known as granulomas before going on to spread the infection themselves (3).

Read the full story.